When patients transition to hospice, deprescribing can be used as a tool to align treatment plans with changing goals of care. Deprescribing is the process of discontinuing inappropriate, ineffective, or unnecessary medications and is often used in an attempt to manage polypharmacy and improve patient outcomes.1 Medications used to treat hypertension (collectively referred to as antihypertensives) should be among those medications considered for deprescribing if they’re ineffective for palliating symptoms or improving quality of life, especially in older patients who are often more susceptible to medication adverse effects (including dizziness and hypotension leading to falls).

Nearly two-thirds of hospice patients are 80 years of age or older and recent figures have revealed that 27% of hospice patients had principal hospice diagnoses of circulatory disease or stroke.2 Many of these patients, and others with different principal diagnoses, take antihypertensives to manage comorbidities. Studies have suggested that older patients with polypharmacy and multimorbidity may experience harmful effects of low blood pressure and the use of multiple antihypertensives.3,4 Recently, researchers in England conducted the OPTIMISE (Optimizing Treatment for Mild Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly) trial to determine if it’s possible to safely reduce the number of antihypertensives taken by patients over the age of 80 without causing clinically significant changes in blood pressure control.5

Many hospice patients are still taking these medications upon admission to hospice and the results of OPTIMISE can be used to support deprescribing decisions.

OPTIMISE

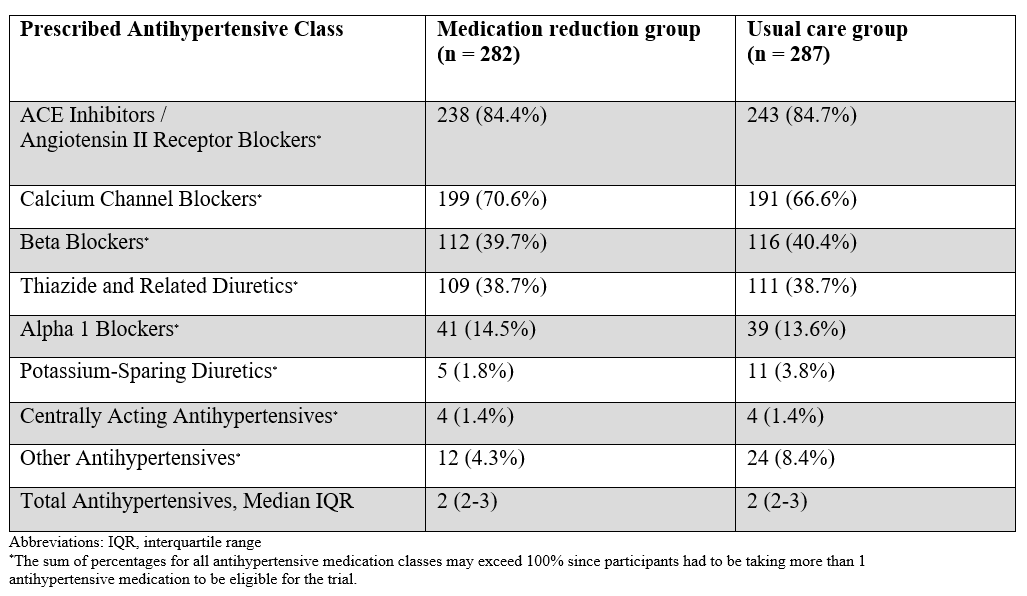

OPTIMISE was designed as a randomized, unblinded, parallel group, noninferiority trial. Primary care physicians enrolled patients who they thought might benefit from deprescribing antihypertensives due to polypharmacy, comorbidity, non-adherence, or frailty. Patients included in the study were at least 80 years old, had a baseline systolic blood pressure (SBP) <150mmHg, and were taking two or more prescribed antihypertensives. They were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either the medication reduction (intervention) group or the usual care (control) group. One antihypertensive was deprescribed in the intervention group and medications were left unchanged in the control group. A breakdown of antihypertensives prescribed for study participants is provided in Table 1. Gradual withdrawal of beta-blockers was encouraged to avoid rebound adrenergic hypersensitivity. Outside of this recommendation, providers were given the authority to decide which antihypertensives to deprescribe and what approach to use (i.e., abrupt discontinuation vs. gradual taper).

Table 1: OPTIMISE: Baseline Prescribed Antihypertensives5

After 12 weeks, medication reduction was found to be noninferior to usual care. Blood pressure control was maintained in 86.4% of patients who underwent medication reduction, compared to 87.7% of patients who continued their usual regimen, a statistically insignificant difference. The mean change in SBP was 3.4mmHg higher in the medication reduction group than the usual care group. Additionally, there weren’t any statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of frailty, quality of life, adverse effects, or serious adverse events at follow up. Medication reduction was maintained in 66.3% of patients in the medication reduction group. This suggests that short-term deprescribing of antihypertensive medications may be possible in some older patients with minimal impact on blood pressure control.

After 12 weeks, medication reduction was found to be noninferior to usual care. Blood pressure control was maintained in 86.4% of patients who underwent medication reduction, compared to 87.7% of patients who continued their usual regimen, a statistically insignificant difference. The mean change in SBP was 3.4mmHg higher in the medication reduction group than the usual care group. Additionally, there weren’t any statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of frailty, quality of life, adverse effects, or serious adverse events at follow up. Medication reduction was maintained in 66.3% of patients in the medication reduction group. This suggests that short-term deprescribing of antihypertensive medications may be possible in some older patients with minimal impact on blood pressure control.

The study had some key limitations, namely participants were handpicked by their physicians, the study was unblinded, some patients reduced or stopped antihypertensives on their own, patients self-reported adverse effects, and medication adherence wasn’t tracked.

OPTIMISE results can be applied in hospice

- The age of study participants reflects that of the majority of hospice beneficiaries.

- The 12-week (84 day) study duration exceeds the average length of stay for hospice patients (76 days).2

- This duration also exceeds the average length of stay for patients with circulatory and chronic kidney disease diagnoses (81.9 days and 38.2 days, respectively). 2

- Deprescribing didn’t lead to clinically significant differences in frailty, quality of life, adverse effects or events, which is meaningful for hospice patients because quality care at the end-of-life is imperative.

- SBP <150mmHg was used as the marker for blood pressure control. This may or may not translate over to the hospice population, as guidelines generally do not pertain to hospice patients and an “ideal” blood pressure hasn’t been established for patients with limited life expectancy. Existing literature fails to identify a blood pressure threshold that indicates when any given patient will become symptomatic so the decision to deprescribe antihypertensives or reduce doses based on blood pressure readings should be individualized.

- Patients in the study were taking two or more antihypertensives. Deprescribing should also be considered for hospice patients taking a single antihypertensive medication.

Deprescribing isn’t always the answer

The conventional role of antihypertensives is to reduce and control blood pressure. Primary hypertension, formerly called “essential hypertension”, doesn’t have a clearly identifiable cause and patients are generally asymptomatic. Severely elevated blood pressure (>180/120mmHg) is classified as hypertensive urgency or hypertensive emergency, the latter of which is characterized by acute end-organ damage. Symptoms of severe hypertension might include headache, dizziness, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, anxiety, or dyspnea.6 Clinical judgement should be used to determine if patients are at risk for developing a hypertensive crisis; we recommend continuing antihypertensives in these patients. After careful consideration of risks and benefits, antihypertensives can generally be deprescribed in hospice patients who take them solely for primary hypertension.

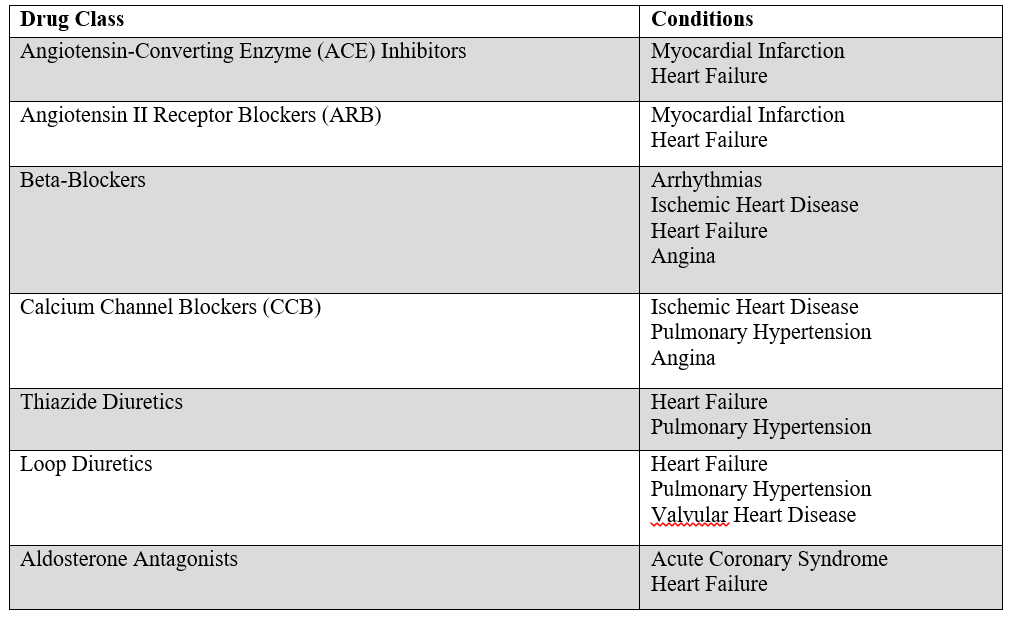

Deprescribing antihypertensives has the potential to improve a terminally ill patient’s quality of life by reducing their pill burden and reducing risk for adverse effects/events. However, these medications are often used to improve symptoms for cardiovascular conditions other than hypertension (Table 2) and they should be continued for as long as the patient desires or tolerates in these cases. Notably, patients with heart failure and recent stroke / myocardial infarction were excluded from OPTIMISE.5Antihypertensives are also used to manage non-cardiac conditions. For example, propranolol is a non-selective beta-blocker used to treat hypertension, but can also be used to palliate symptoms of atrial fibrillation, angina, migraine, tremor, and anxiety. We recommend that antihypertensives used for symptom palliation remain in place as long as they are effective and tolerated.

Table 2: Antihypertensive Medications with Palliative Benefits for Select Cardiovascular Conditions7-13

Takeaway: Certain hospice patients stand to benefit from deprescribing antihypertensive medications. Deprescribing antihypertensives used for the sole purpose of treating primary hypertension may be possible with minimal impact on blood pressure control, and should be considered for patients who are unlikely to experience symptoms when treatment is withdrawn.

References

- Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J, Hilmer S. A systematic review of the emerging definition of ‘deprescribing’ with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol.2015;80(6):1254–68. doi:1111/bcp.12732

- https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2018_NHPCO_Facts_Figures.pdf (accessed June 2020)

- Benetos A, Labat C, Rossignol P, et al. Treatment With multiple blood pressure medications, achieved blood pressure, and mortality in older nursing home residents: the PARTAGE study. JAMA Intern Med.2015;175(6):989-995. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8012

- Tinetti ME, Han L, Lee DS, et al. Antihypertensive medications and serious fall injuries in a nationally representative sample of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):588-595. doi:1001/jamainternmed.2013.14764

- Sheppard JP, Burt J, Lown M, et al. Effect of Antihypertensive Medication Reduction vs Usual Care on Short-term Blood Pressure Control in Patients With Hypertension Aged 80 Years and Older: The OPTIMISE Randomized Clinical Trial. 2020;323(20):2039–2051. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4871

- heart.org (accessed June 2020)

- McGuinty C, et al. Heart failure: A palliative medicine review of disease, therapies, and medications with a focus on symptoms, function, and quality of life. Journal of Pain & Symptom Management.doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.12.357

- LeMond L, et al. Palliative care and hospice in advanced heart failure. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2011;54(2):168–178.

- Colucci WS. Secondary pharmacologic therapy in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) in adults. UpToDate (Lit review current through Feb 2020, accessed March 2020).

- Xuming DAI, et al. Stable ischemic heart disease in the older adults. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology.2016;13:109-114. doi:11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.02.013

- Zipes DP, et al. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

- Management of thoracic aortic aneurysm in adults. UpToDate (accessed June 2020).

- Secondary pharmacologic therapy in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) in adults. UpToDate (accessed June 2020).

Written by:

Julie Ha Nguyen, PharmD Candidate, 2021

University of Iowa College of Pharmacy

Reviewed by:

John Corrigan, PharmD

Clinical Pharmacist, OnePoint Patient Care