In 2014, the American Pain Society (APS), College on Problems of Drug Dependence, and the Heart Rhythm Society released clinical practice guidelines that focused primarily on safe methadone prescribing practices.

The APS guidelines included information regarding patient education, dosing and titration methods, recommendations for electrocardiograph (ECG) and adverse event monitoring. Unfortunately, these guidelines didn’t account for patients with limited life expectancies. Since there is less utility in aggressively monitoring this patient demographic, in 2015, a panel of 15 hospice and palliative care (HPC) experts convened to develop their own guidelines on methadone treatment for patients with life-limiting illnesses. Following a systematic search and review of methadone literature, along with evaluating the APS guidelines, their guidance aimed to maximize benefits and minimize risks for these patients. Their opinions, “Safe and Appropriate Use of Methadone in Hospice and Palliative Care: Expert Consensus White Paper”, were published in the March 2019 issue of the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. The following is an excerpt of their recommendations including the major differences between the two guidelines.

Patient Characteristics

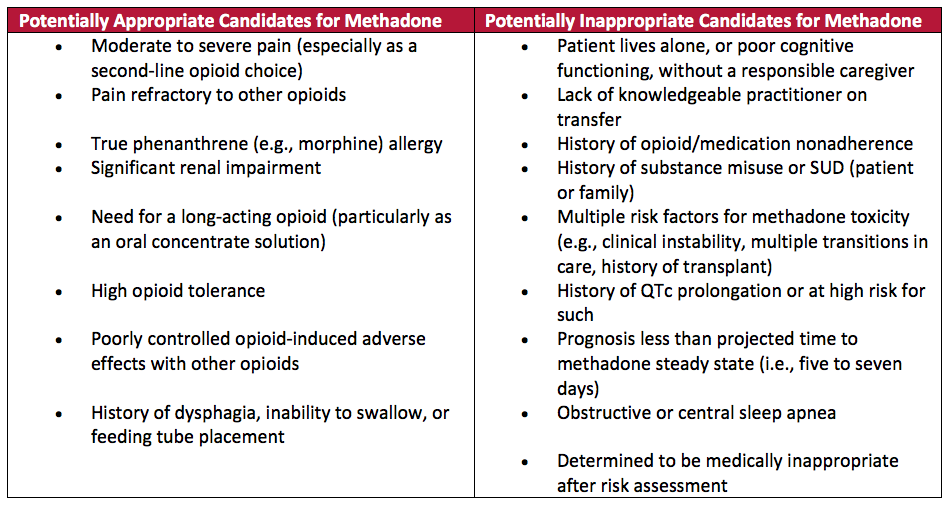

To help classify patients as suitable candidates, the HPC group identified specific patient characteristics to determine their viability for methadone treatment (Table 1). They also highlighted certain conditions that can potentially increase the risk of methadone toxicity—warranting additional precautions such as: starting with low doses, waiting 10-14 days between increasing doses for patients with severe liver impairment and avoiding co-prescribing methadone with benzodiazepines in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. For some patients, such as illicit drug users, the safest option may be to withhold methadone therapy altogether.

Table 1: Patient Selection for Methadone Therapy

Dosing

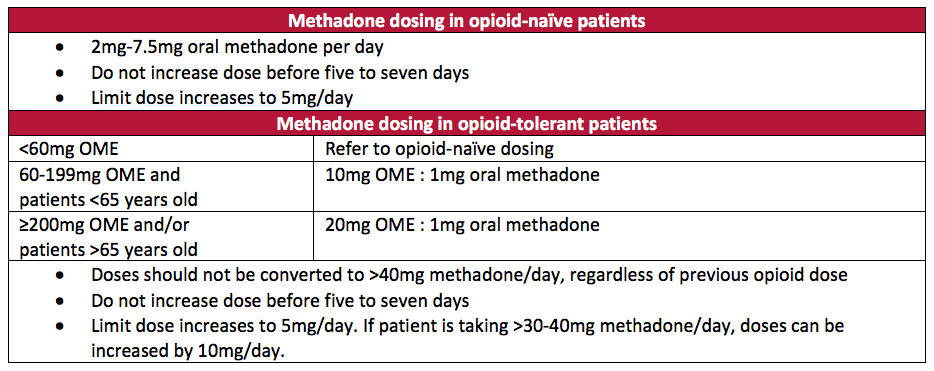

Only a few subtle differences were found between the APS and HPC guidelines in regards to methadone dosing.

Both groups agree that:

1) The initial methadone dose in opioid-naïve patients, including those receiving up to 40-60mg/day of oral morphine equivalents (OME), shouldn’t exceed 7.5mg/day.

2) Dose increases shouldn’t exceed 5mg/day.

3) Clinicians should wait at least 5 to 7 days before increasing doses, which should allow enough time for most patients to achieve steady state.

To allow for lower starting doses for opioid-naïve patients, the HPC group specifically recommended an initial dose range of 2-7.5mg/day.

APS gave relatively vague recommendations to convert opioid-tolerant patients to methadone, citing various equianalgesic dose ratios and recommending a reduction in the calculated equianalgesic dose by 75-90%. The HPC group, on the other hand, suggested specific conversion ratios that could potentially account for incomplete cross-tolerance, and thus, negating the need to reduce the calculated dose (Table 2). The HPC group also recommended using a more conservative ratio for patients over 65 years old.

See Table 2 for a summary of the HPC group’s dosing recommendations.

Table 2: HPC Consensus Methadone Dosing Recommendations

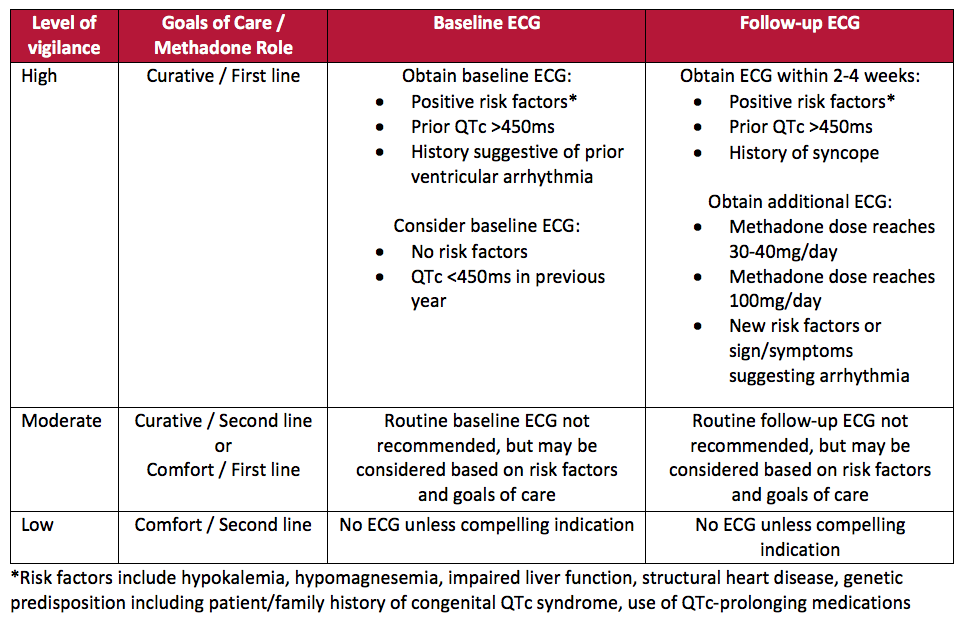

Cardiac Monitoring

Since methadone use is associated with risk of QTc interval prolongation, the APS guidelines strongly recommended obtaining a baseline ECG, as well as follow-up monitoring, in patients with high risk factors for QTc prolongation. APS also advised clinicians to avoid prescribing methadone if QTc is greater than 500ms. While acknowledging the different risk-benefit profiles and treatment goals for patients with life-limiting illnesses, the HPC group made distinct recommendations to consider the availability of ECG records, prognosis, type of pain, and anticipated methadone total daily dose. They defined three categories of monitoring vigilance depending on the role of methadone and the patients’ goals of care (Table 3).

Table 3. HPC Consensus Recommendations for ECG Monitoring with Methadone Use

Other Monitoring

The HPC group emphasized the importance of patient and caregiver education and involvement in the monitoring process. For efficacy, they recommended close monitoring for any signs/symptoms of overdose. With that, they also suggested to monitor patients for a minimum of 5 days following methadone initiation (or titration) and advocated for extending this monitoring period to up to 14 days in older patients, since it can take them longer to reach steady state. This period was extended from the 3 to 5 day monitoring period suggested in the 2014 APS safety guidelines. Since drug interactions with methadone can result in enhanced opioid effects (eg., sedation and respiratory failure) and other non-opioid effects (eg., QT prolongation), the HPC group also stressed the importance of routinely reviewing patients’ medication lists to assess for the addition or elimination of medications. This recommendation for more frequent monitoring is a reflection of the unique characteristics and needs of all hospice and palliative care patients.

Conclusion

The 2014 guidelines from Chou et al. (APS) have undoubtedly helped improve methadone safety. The Consensus White Paper (HPC), on the other hand, represents an evolution of these guidelines with more specific advice for patients with life-limiting illnesses—a welcome addition for those of us that wish to provide unsurpassed quality of care for hospice patients!

Written by: Jake Felckowski, PharmD Candidate 2019, University of Iowa

Reviewed by: Melissa Corak, PharmD, Clinical Pharmacist, OnePoint Patient Care

References:

Chou R, et al. Methadone Safety: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American Pain Society and College on Problems of Drug Dependence, in Collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society. Journal of Pain. 2014;15(4):321-337.

McPherson ML, et al. Safe and Appropriate Use of Methadone in Hospice and Palliative Care: Expert Consensus White Paper. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2019;57(3):635-645.e4.